Performance Writing is one of those unwieldy terms – not quite familiar enough for us to assume we already know what it means, not quite descriptive enough for us to simply guess. Fitting, then, that this term refers to a field with a willful unwillingness to commit to fixed definitions. In Thirteen Ways of Talking about Performance Writing, a lecture given to all first year undergraduates of Dartington College of Arts on Tuesday 22nd November 1994, in the inaugural term of a new undergraduate degree called Performance Writing, John Hall advocates for definings rather than definitions:

Like ‘writing’ ‘defining’ can best be treated as a gerund, catching the present tense of the verb up into a noun, without losing the continuous dynamic of the verb: the process of the act of defining. If the process were to end in resolution we would move the defining into definition. We would know.

We won’t.

John Hall performing at Performance Writing Weekend 2012, Arnolfini, Bristol, May 2012.

To consider the term Performance Writing in explicitly Performance Writing terms, the intelligibility of the term is intertwined both with the context of its production and of its consumption. At one time those were one in the same. Dartington College of Art was a specialist performance arts institution which operated in South Devon, England, from 1961-2008. It evolved out of a particular and somewhat peculiar mixture of the Dartington Hall experiment in rural regeneration led by Dorthy and Leonard Elmhirst in the 1920s, and the alternative education experiments of both the Dartington Hall School and Schumaker College, which both operated on the Dartington Estate, and the Steiner School movement. Dartington College of Art was also influenced by the cross-disciplinarity and collective engagement and post-modern modes of writing which emerged from Black Mountain College in North Carolina in the 1950s. The term Performance Writing was in use within the Theater department at Dartington as early as 1987. The discussions which led to the development of Performance Writing as a set of independent practices at Dartington began in 1992. The BA was founded by John Hall in 1994, the MA in 1999, and practice-led PhD research in Performance Writing also began at this time.

Steve McCaffery and cris cheek performing Carnival live at Birkbeck, London, UK, 06 June 2012

Performance Writing pedagogy, methodology, and practices were developed by active practitioner-lecturers at Dartington, including John Hall, Ric Allsopp, Caroline Bergvall, Aaron Williamson, Brigid Mc Leer, Alaric Sumner, Redell Olsen, cris cheek, Peter Jager, Barbara Bridger, Melanie Thompson, Jerome Fletcher, and many others, and enriched by an program of visiting artists from around the world. From the outset, Performance Writing has taken a consistently broad and overtly interdisciplinary approach to what writing is and what writing does in a range of social and disciplinary contexts, exploring writing and textual practice in relation to visual art, digital media, installation, performance, collaborative practices and sound/audio work, as well as book art and page-based media. The democratic, inclusive, and above all extensible nature of Performance Writing methodology has led to its adoption and adaptation by both independent and academic researchers, practitioners, pedagogs, and institutions in places as far flung as: Aarhus, Denmark; Berne, Switzerland; Oakland, California; Banff, Canada.

Erin Robinsong performing at In(ter)ventions: Literary Practice at the Edge, The Banff Centre, February 2011

In the UK, Performance Writing methodologies and sensibilities have spread – primarily through graduates of the the program at Dartington – into a rich diversity of artistic forms and institutional formulations, including but by no means limited to: performance in/with digital literature, as explored by Jerome Fletcher in the context of the HERA-funded research project ELMCIP; thematic multi-diciplinary writing workshops, as led by Devon-based Writing&; digital glitch literature and electronic voice phenomena performance, as explored by Liverpool and London based Mercy; conceptual writing and small press publishing, as explored by Leeds based Nick Thurston, and language and voice as explored by Bristol-based salon series Tertulia. In 2005 Text Festival in Bury hosted Partly Writing 4: Writing and the Poetics of Exchange, a session with which a number of Performance Writing people were involved. Text Festival continues to present work which is profoundly ‘Performance Writing’ in nature. Affinities with Performance Writing are also evident, though not in name, at Birkbeck, at Royal Holloway, and in the MFA in Art Writing led by Maria Fusco at Goldsmiths University (though information about this program is not turning up on the website any more, which does not bode well). Performance Writing sensibilities are also evident the Writing-PAD initiatives at Goldsmiths University, which include the publication of the Journal of Writing in Creative Practice, which will put out a special issue dedicated to Performance Writing late 2013 or early 2014. And in Open Dialogues: critical writing on and as performance, a writing collaboration that produces writing on and as performance founded by Rachel Lois Clapham and Mary Paterson in 2008. Performance Writing sensibilities also appear to be emerging within the CRASSH research centre at Cambridge University, which recently held the excellent seminar: Beyond the authority of the ‘text’: performance as paradigm, past and present.

Performance Writing as paradigm (at present) appears to be expanding from a disappearing centre (its past). Which is to say, Performance Writing is currently undergoing a paradigm shift.

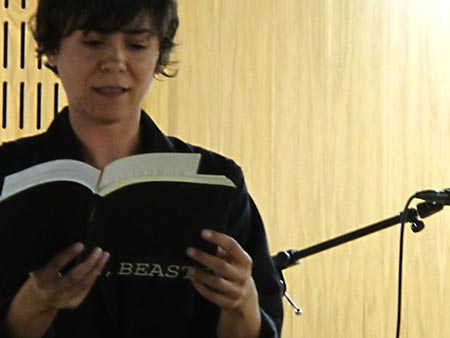

Oana Avasilichioaei performing We, Beasts at Environmental Utterance, University College Falmouth, 2 September 2012.

In 2008 Dartington College of Art merged with University College Falmouth, Cornwall. The relocation to Cornwall was completed in 2010, at which point, University College Falmouth, incorporating Dartington College of Art, as the institution became known, ceased recruitment to the BA Performance Writing. It has not resumed. The MA Performance Writing, led by Jerome Fletcher, continued to run at Arnolfini, a major European art and performance centre in Bristol, UK. Two Performance Writing Weekend festivals have been held at Arnolfini: PW10, and PW12. Recruitment to the MA Performance Writing was ceased in 2012. It has not resumed. Performance Writing continues at the postgraduate and research level at what is now called Falmouth University, where I am now nearing the completion of a practice-led PhD, which will in fact be awarded by University of the Arts London, but which in my mind remains entwined with the pedagogy, methodology, and practices of Performance Writing, Dartington College of Art.

What’s in a name anyway?

Earlier in this post I proposed that the intelligibility of the term Performance Writing is intertwined both with the context of its production and of its consumption. How can this term and the sets of practices it refers to be understood in its current institutional context? On the current Falmouth University website, the four slight paragraphs dedicated to the Performance Writing Research Group page trail off with an ellipsis… All trace of Performance Writing programs and pedagogy past have been erased from both the Dartington and the Falmouth websites. As there is no new student intake, Performance Writing is not being taught at either the undergraduate or graduate levels. Thus, Performance Writing is divorced from both the context of its own production and the possibility of its own consumption.

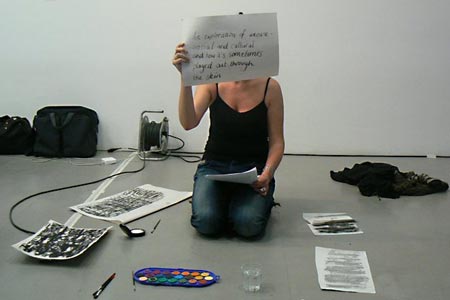

Writing & the Body workshop, Arnolfini, Bristol, 2012.

In addition to its willful unwillingness to commit to fixed definitions, Performance Writing has long eschewed any suggestion of a fixed corpus, preferring rather to assemble a fresh corpus around each new set of questions posed. Perversely, my question here is: what comprises the corpus of writing on Performance Writing? Paradoxically, as Performance Writing expands and evolves in new contexts, its corpus grows exponentially, but so too do its variables. Art Writing. Conceptual Writing. Performance Poetry. Sound Poetry. Digital Literature. Alt Lit. As these terms and conditions shift their names become many, which makes writing on writing in the field harder and harder to Google.

Here then is a collection of texts which directly address (or perform) Performance Writing in the Dartington sense of the term. This list is neither means exhaustive, nor fixed. Please. Send names and links and references. I’ll gladly add them. Note that by the time you read this list it may have been amended from what it once was and after you read it it may yet be amended again. Already I am indebted to John Hall for additions to this list and clarifications on points in this post as a whole:

Ric Allsopp, “Performance Writing,” in PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art. Vol. 21, No. 1, 1999. pp. 76-80.

Caroline Bergvall, What do we mean by Performance Writing? (PDF) a keynote address delivered at the opening of the first Symposium of Performance Writing, Dartington College of Arts, 12 April 1996.

Barbara Bridger, Dramaturgy and the Digital in Exeunt Magazine, 2013.

Barbara Bridger & J. R. Carpenter, “Call and Response: Toward a Digital Dramaturgy,” in Journal of Writing and Creative Practice. Goldsmiths, London, UK (forthcoming)

David Buuck, What is performance writing? in Jacket2, 2013.

J. R. Carpenter, Performing Digital Texts in European Contexts, commentary column on Jacket2, 2011.

J. R. Carpenter, Where performance and digital literature meet…, The Literary Platform, May 2012.

cris cheek, Reading and Writing: the Sites of Performance in How2, Volume 3, Issue 3, 2009.

Rachel Lois Clapham, assemblage, Inside Performance Volume 24. no.1, 2011

Jerome Fletcher, Performing …Reusement. E-composition / Decomposition (PDF), inCybertext Yearbook, University of Jyväskylä, 2010.

Maria Fusco, Michael Newman, Adrian Rifkin and Yve Lomax, 11 Statements Around Art Writing, Freize, 2011.

John Hall, Performance Writing: a Lexicon Entry, in A Lexicon: Performance Research Volume 11, No. 3. September 2006. pp. 89–91.

John Hall, Thirteen Ways of Talking about Performance Writing, Plymouth: PCAD, 2008.

John Hall, Essays on Performance Writing, Poetics and Poetry Vol. 1. On Performance Writing, with pedagogical sketches, forthcoming from Shearsman Books, October 2013.

Carl Lavery & David Williams eds, Good Luck Everybody: Lone Twin – Journeys, Performances, conversations, Performance Research Books, 2011.

Della Pollock, Performing Wiring (PDF), in The Ends of Performance. eds. Peggy Phelan, Jill Lane, NY: NYU Press, 1998. pp 73-103

Alaric Sumner, Writing & Performance, PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art, PAJ 61 (Volume 21, Number 1), January 1999

Three recent anthologies which have no idea how Performance Writing they are.

In addition to the above list, there are numerous works which, although not expressly performance writing in name, are profoundly performance writing in nature. Listed here are but a very few of those:

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, Harvard University Press, 2002.

Deleuze and Guattari, Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature, U of Minnesota Press, 1986.

Jean-Jacques Lecercle, A Marxist Philosophy of Language. trans. Gregory Elliot. Leiden & Boston: Brill, 2006.

W. G. Sebald, Rings of Saturn, Vintage, 2002.

Situationist International Text Library

Gertrude Stein, How To Write, NY: Dover, 1975.

McKenzie Wark, A Hacker Manifesto. (PDF) Harvard University Press, 2004.

The field of Performance Writing has of course produced a rich corpus of creative works, far too numerous to mention here.

For more information about Performance Writing, and/or to participate in ongoing workshops, events, and activities, visit:

Performance Writing entry on Wikipedia

(this page needs updating)

Performance Writing group on Facebook

(1,157 followers at the time of this writing)

Writing & multi-diciplinary writing workshop series

(led by former Dartington Performance Writing Faculty)

Tertulia

(Bristol-based salon series)

In(ter)ventions: Literary Practice at the Edge residency program at The Banff Centre

(where I am Performance Writing Faculty)