As an artist and author of both print and digital literature I have made extensive use of archival materials over the past twenty years, incorporating ‘found’ images from old text books and ‘borrowing’ source code from dusty corners of the Web. I will aim to frame these acts of appropriation as contributions to a larger cultural project during Friction and Fiction: IP, Copyright and Digital Futures, a one day symposium taking place at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London 26 September 2015.

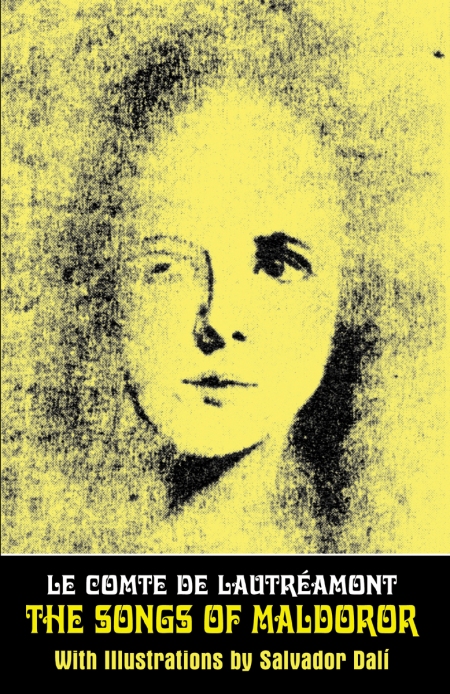

In 1870 Le Compte de Lautréamont famously wrote: “Plagiarism is necessary. It is implied in the idea of progress. It clasps the author’s sentence tight, uses his expressions, eliminates a false idea, replaces it with the right idea.” In The Beach Beneath the Street: The Everyday Life and Glorious Times of the Situationist International, McKenzie Wark observes that Lautréamont “corrects, not back to a lost purity or some ideal form, but toward to a new possibility” (2011 34). In this spirit, let’s use Lautréamont’s expression, but eliminate the false idea of an assumed male author:

“Plagiarism is necessary. It is implied in the idea of progress. It clasps the author’s sentence tight, uses her expressions, eliminates a false idea, replaces it with the right idea.” J. R. Carpenter

In the 1920s Lautréamont was re-discovered by the Surrealists, who hailed him as a patron saint. In the early 1950s news broke that some of the most poetic passages of Lautréamont’s most well-known work, The Songs of Maldoror (1869), had been plagiarised from text books. I’d love to say this is where I got the idea from, but I’d been plagiarising text books long before I’d ever heard of Lautréamont.

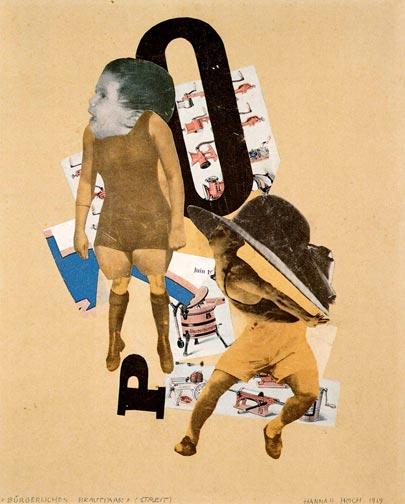

The Letterist International credited Lautréamont with the discovery of a method they termed détournement. To détourne is to detour, to lead astray, to appropriate — not a literary form, as in a style, a poetics, or a genre, but rather a material form, as in a sentence, a book, a film, a canvas. In this material approach the Letterists lagged decades behind the Dadaist, Constructivist, and Surrealist collage and photomontage artists of the 1920s.

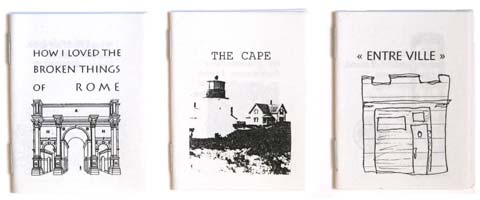

I went to art school. I came to writing through the material practices of photographing, photocopying, cutting with scissors, and pasting with glue. Hannah Hoch was my hero. Her lover Raoul Hausmann was pretty great too. I was mesmerised by the strange relations between image and text in the collage novels of Max Ernst (1891–1976), as was another of my art school icons, Joseph Cornell. At the recent exhibition of Cornell‘s work at the Royal Academy in London I was delighted to discover that Cornell had appropriated a black and white image of a girl balancing a stack of suitcases on her head from the front page of my website.

One of my earliest web-based works, Mythologies of Landforms and Little Girls was first published in a literary journal in 1995, but I remained unsatisfied with the fixed order of the story. In 1996 I made a non-linear HTML version in which readers could move through the story their own way. Most of the images and subtexts come from a civil engineering handbook. The deadpan technical descriptions of dikes, groins and mattress work add perverse sexual overtones to the otherwise chaste first-person narrative. Between the diagrammatic images and the enigmatic texts, a meta-narrative emerges wherein the absurd and the inarticulate, desire and loss may finally co-exist.

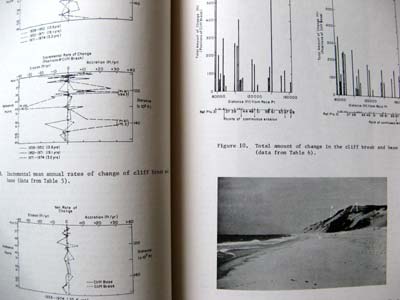

I built The Cape in 2005, but some of the sentences had been kicking around in my brain since the early 1990s. I couldn’t quite figure out what to do with them until came across a used copy of an Environmental Geologic Guide to Cape Cod National Seashore published by the University of Massachusetts in 1979, around the time of my one and only trip to Cape Cod to visit a grandmother I barely remember. I used photographs, charts, graphs and maps from the Geologic Guide as stand-ins for non-existent family photos — a surrogate family album. I used DHTML timelines produce a silent, jumpy, staggering effect reminiscent of the Super-8 home movies in which I’d always longed to star. The Cape has since been published in the Electronic Literature Collection Volume One, under a Creative Commons licence, and as a zine, in which images from the Geologic Guide mingle with diagrams appropriated from children’s text books.

In more recent works, I have turned my acquisitive attention toward the appropriation of literary texts.

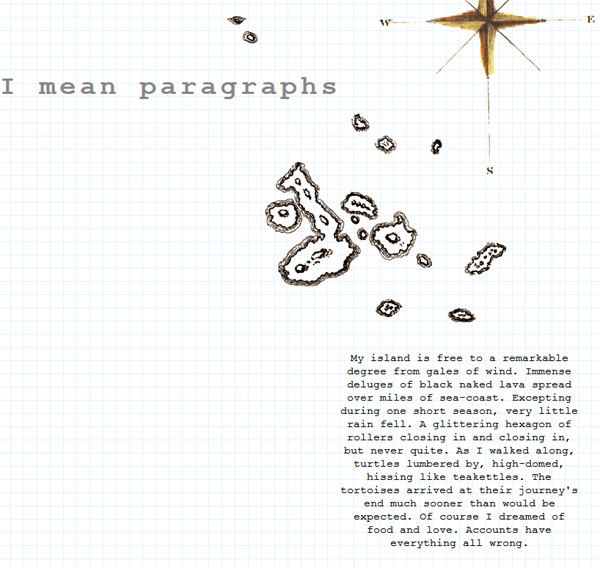

In …and by islands I mean paragraphs (2013), small paragraphs generated by JavaScript draw upon variable strings containing fragments of literary texts harvested from a vast corpus of essays, plays, poems, novels, and travel writing on the topic of islands, including a number of works which have already borrowed from each other. My aim is not to claim these fragments of literary works as my own, but rather, to make their inner workings more overt. For example, whilst the title of Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “Crusoe in England” (1971) makes clear reference to Daniel Defoe’s novel Robinson Crusoe (1719), nowhere within the poem does Bishop acknowledge that the textual topography of her Crusoe’s island borrows heavily from Charles Darwin’s descriptions of the Galapagos Islands in The Voyage of the Beagle (1838), a book which Bishop admired. And why should she?

McKenzie Wark argues: “For past works to become resources for the present requires… their appropriation as a collective inheritance, not as private property” (2011: 37). In …and by islands I mean paragraphs I have clasped the authors’ sentences tight. I have used expressions from both Bishop and Darwin. I have eliminated the false idea that either text is fixed, advocating instead for the bright idea that literature is our and we should use it however we want.

Incorporation of appropriation, variation, and transformation into the process of composition results in writing that is always on the cusp of becoming something else.