I was thrilled when Aurelea Mahood wrote to me back in September to say she’d be teaching my piece, The Cape, in her E-literature class at Capilano University, on Friday, October 10th, 2008. I would have come into the class to speak about the work in person, but Capilano University is in North Vancouver, British Columbia and I am in Montreal, Quebec. To bridge this vast distance, Aurelea came up with a creative solution: she invited me to be a guest blogger in her class.

In this blog post to CultureNet @ CapilanoU, I will present some background information about the creation of the work that wouldn’t necessarily be apparent from viewing/reading it. The students will then discuss and pose questions via blog comments, which I will attempt to answer in a timely manner. Here, then, is (one version of) the back-story of The Cape.

I built the web iteration of The Cape over the course of 10 days in August 2005, but some of the sentences in The Cape have been kicking around in my brain since the early 1990s. When I started writing the text of The Cape I was studying Studio Art, with a concentration in Fibres & Sculpture, at Concordia University in Montreal. At the time, I had no idea what to do with such seemingly simplistic yet somehow ponderous sentences as: My grandmother Carpenter lived on Cape Cod in a Cape Cod House. My uncle also lived on Cape Cod, but not in a Cape Cod House.

I was quite preoccupied with the conjoined notions of memory and place at the time. In the mid 1990s made a number of installations, interventions and artist’s books containing some of the same sentences that now appear in The Cape. This body of work, collectively entitled, “The Influence of a Maritime Climate,” was based on a passage from Michel Foucault’s Madness & Civilization:

“In the classical period the melancholy of the English was easily explained by the influence of a maritime climate, cold, humidity, the instability of the weather; all those fine droplets of water that penetrated the channels and fibers of the human body and made it lose its firmness, predisposed it to madness.”

Michel Foucault, Madness & Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason, trans. Richard Howard, NY: Vintage, 1988, pages 12-13.

I grew up in a maritime climate, in rural Nova Scotia. My father ran a Cape Islander (fishing boat) in the Bay of Fundy. He was English. He left when I was eight and I never saw him or his mother, my grandmother Carpenter, again. I don’t have a photograph of my grandmother Carpenter. If I did, I would insert it here. It’s true that I don’t have a photograph of my grandmother Carpenter, but I do have a photograph of her house, which is indeed a Cape Cod house. In the days before digital photography, a physical photograph had a certain authority – especially if it happened to be the only extant souvenir of a relative disappeared. I realized, when I wrote the above quoted sentence, that I had come to think of the photograph of my grandmother’s house as a photograph of her.

I hadn’t given my paternal grandmother’s English-ness, and thus my own English-ness, much thought. I was much more preoccupied with my maternal grandmother, a Jewish, Hungarian, Yiddish-speaking, first-generation American immigrant to the Lower East Side of New York City, with whom I had spent every summer, when I was growing up. Since moving to Montreal I had been attempting to put my rural, maritime origins behind me. Foucault’s phrase “the influence of a maritime climate” and the preposterous notion that “all those fine droplets of water that penetrated the channels and fibers of the human body” would predispose me – a half-English former Maritimer – to madness, opened the door, for me, to the possibility of writing fiction.

This was excellent timing as I had just discovered the Internet. I got my first Unix account in 1993, and promptly began posting fictional accounts of myself and my alternate pasts to various alt.arts USENET groups. For more about the many hours I spent in the Concordia University Unix lab, surrounded by computer science students, making stuff up off the top of my head, and how that led to a three-year stint managing a web development team for a multi-national software company, see: A Brief History of the Internet as I Know it So Far [2003]:

The Internet was totally textual back then. It had no interface. The joke of the day was, On the Internet no one knows you’re a dog. Everyone was talking about gender politics and how, on the Internet, you could role-play and construct your own identity. At the same time that everyone was obsessed with sexuality they were all claiming disembodiment, which seemed like a contradiction, even then.

“A brief history of the Internet as I know it so far,” J. R. Carpenter, Fish Piss, Vol. 2, No. 4, Montreal, QC, Fall/Winter 2003/2004.

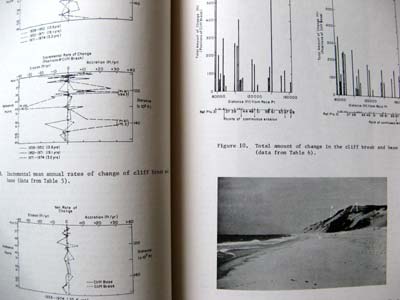

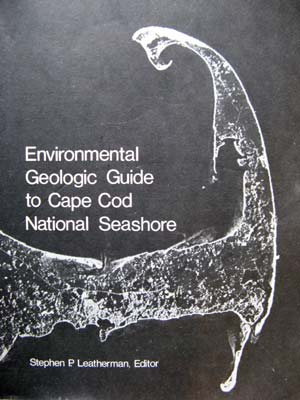

Around the same time as I was reading too much Foucault for my own good, turning my paternal grandmother into a fictional entity and logging into MUDs and MOOs to tell nonsensical stories to total strangers, I came across a used copy of: Stephen P. Leatherman, Editor, Environmental Geologic Guide to Cape Cod National Seashore; Field Trip Guide Book for the Eastern Section of the Society of Economic Paleontologists & Mineralogists, National Park Service Cooperative Research Unit, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Mass., 1979.

My Family Album

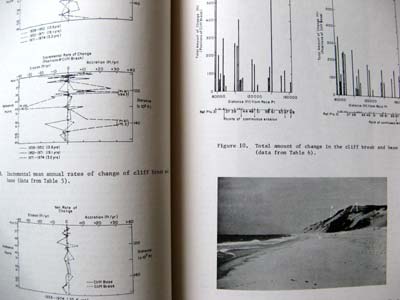

The Geologic Guide contained many photographs of Cape Cod. I had only had the one photo of my grandmother’s house. The Guide was published in 1979, around the time of my one and only brief visit to Cape Cod. The only time we went to visit it was winter but we walked on the beach anyway. It occurred to me immediately to use the Geologic Guide photographs, charts, graphs and maps as stand-ins for non-existent family photos, and the Guide itself as a surrogate family album. This was much more interesting to me than the truth of what ever my family history had been. If only there was some way to put pictures on the Internet!

I was attracted to the black and white aesthetic of the Environmental Geologic Guide to the Cape Cod National Seashore. Before computers were readily available, I worked extensively with photocopiers. For more about how I almost got fired from my job in the Concordia University Fine Arts Slide Library for abusing their photocopy machine for artistic purposes, see this (only slightly) tongue-in-cheek essay: A Little Talk About Reproduction [2004]:

I can’t say that I woke up one morning and found myself in bed with the computer. My love affair with art was a youthful thing, impractical and highly idyllic. But my tryst with the photocopier was fully sordid and adult. We met at the office. The photocopier made itself invaluable to me by enlarging, reducing and reproducing endlessly. I would tell my friends that I had to work late. I would stay for hours after closing, making collages seemingly out of nothing, liberated in no uncertain terms, or so I thought, from physicality and from preciousness. Guilty of white lies, laziness and copyright infringement, I would scrub my toner stained hands before leaving the office.

“A Little Talk About Reproduction,” Fish Piss, Vol. 3, No. 1, Montreal, QC, Fall 2004.

It was winter but we walked on the beach anyway.

I graduated from art school in 1995, and made my first web project later that year at a residency at The Banff Centre for the Arts (as The Banff Centre was called back then). Many of my early web projects were in black and white because that’s what colour photocopies come in. The images in Fishes & Flying Things [1995], Notions of the Archival in Memory and Deportment [1996] and Mythologies of Landforms and Little Girls [1996] were all scanned from my massive collection of photocopies of diagrams and maps.

Although I have since made many works in colour, The Cape [2005] returns to the black and white aesthetic of those early works. This is in part because the Geologic Guide is entirely black and white, and in part because I had actually begun the project at the same time as those works. The Cape visually resembles those earlier works, but uses code elements that did not exist in 1995, such as IFRAMEs and DHTML timelines. The small, moving images you see on some pages of The Cape – on the Sound carries, especially in winter, page, for example – are actually large, still images being pushed behind a small IFRAME window by a long DHTML script. This means, in effect, that the text is moving the image. The use of DHTML timelines produces a silent, jumpy, staggering effect reminiscent of a super-8 film, which is how home movies would have been made in 1979.

The main reason it took me so long to create the web iteration of The Cape was not a technical one at all. It was, rather, a literary conundrum. I didn’t know how to make sense of those deceptively simple sentences. What a boring story this is. I revisited The Cape as a short story many times over the years. For a long time I thought the story had to be longer. Then I finally realized it had to be shorter. The shorter a story is, sometimes, the longer it takes to write. In the spring of 2005 an editor invited me to submit a very short story to a very small magazine. I sent The Cape, along with some diagrams from the Geologic Guide.

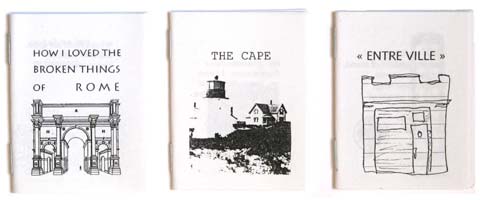

Print Copy of The Cape

After a decade of editing, the story finally seemed finished when I saw it in print. I immediately set to work on the electronic version. Months after the launch of The Cape, I created a mini-book version – a small, photocopied zine containing the text of The Cape and images from the Geologic Guide. The mini-book iteration of The Cape is exactly the sort of thing I would have made in art school. Finally, the work had come full circle.

3 Mini-Book Iterations of Electronic Literature Works

The Cape has been included in the Electronic Literature Collection Volume One, the Rhizome ArtBase, BathHouse, function:feminism and, most recently, an exhibition in Tasmania called Hunter/Gatherer. I’ve had a wide range of responses to the work. Some people are convinced it’s a true story, because it’s in the first person. Some are convinced I am an American, because Cape Cod is such an iconic American landmark. One reviewer recently wrote with great conviction that I had lived on Cape Cod, and I was a nostalgic for writing about it. I am nostalgic for lots of places, but not for Cape Cod. Cape Cod may well be a real place, but as far as I am concerned, The Cape is fictional.

I thank you for this opportunity to think back to these sentences of The Cape first entered my head and how they have shifted over time. And I thank your for your interest in and close reading of the piece. I will leave you now with this write-up of The Cape from Scot Cotterell, curator of Hunter/Gatherer:

Hunter/Gatherer: curatorial essay by Scot Cotterell

Hunter/Gatherer: Search Theory or Data Bodies in X.s.

J.R.Carpenter’s The Cape seeks to convolute fact and fiction by taking us on a user-controlled journey of fragmented narrative. The combination of formal, informal and sometimes seemingly inconsequential information activates an in-between state, a suspension of sorts where information seems ordered in meaningful ways, but we are never quite sure. For example, ‘Cape Cod is a real place, but the events and characters of THE CAPE are fictional. The photographs have been retouched. The diagrams are not to scale’ appears alongside anecdotal familial histories, ‘My grandmother Carpenter lived on Cape Cod, in a Cape Cod House. My uncle also lived on Cape Cod, but not in a Cape Cod house’. Using field trip guide books and environmental guides, old maps, diagrams, and collected source code filtered through a low-tech aura The Cape gracefully addresses the tension between the knowing of and mapping of place and memory by bringing together the connotative powers of fact and fiction.

. . . . .