A Novel in Point-Form With No Names

Despite many blizzard-related delays, I arrive in New York more or less on time for dinner. My Poor Host listens patiently to the long version of the Greyhound Prisoner Release Programme (see previous post). I tell him the story three times. Trying to nail down the dialogue, I explain. Then I sleep, a turning point in the plot, after all those sleepless weeks at Yaddo.

I spend the morning writing out my Escape From Yaddo adventure. In the afternoon I have coffee with a French Painter friend from Yaddo at the apartment of a Turkish Fibre Artist friend from Ucross. They know each other from before. Setting (important for a later scene): a sunny tenement turned charming studio on Spring Street at Bowery.

At 5PM I meet a Russian Novelist friend at Penguin. He introduces me to his coworkers as his cousin. There’s an office party going on. Though we behave like cousins – interrupting and making fun of each other whilst stealing copious amounts of books and wine and cheese – no one believes we are actually cousins. Perhaps we have too much fun to be family. We head to Astoria for dinner.

Two Jews walk into a Czech Bar during Pork Festival Week. Our vegetarian waitress fights the kitchen staff and wins a plain dumpling for us. It’s hard for us during Pork Fest Week, she says. The Russian Novelist says: I did a smart thing – I didn’t fall in love with you. Yes, very clever of you, I agree. Because now we’re good friends. We buy some Bavarian Pilsner and head to his sub-basement apartment where we spend the rest of the evening reading comics. The Russian Novelist also draws, he reminds me, and is a big fan of Thurber. And a gentleman. He sleeps on the couch and I get the bed.

Breakfast is ready, the Russian Novelist says. Turkish coffee in Moldavian glasses. There’ll be a war! I say. But breakfast proceeds peaceably.

We’re late to meet our Croatian Novelist friend for coffee the East Village, his own fault for changing our date to a time too early for us. The Croatian Novelist, having been cast in the father role, offers up this sage advice: You should sell some good books and then come and teach in Saint Petersburg. Oh, such good advice. Thank you, thank you, really, we had not known but yes, now that you mention it, what a good idea, that’s just what we’ll do. He’s good-natured, our Croatian Novelist friend. So we tease him.

A Russian Novelist, a Croatian Novelist and a very short story writer walk into Odessa. The Pirogues are prefabricated. The ceiling is red. The banquette pleather rent. We reminisce about how we met two years ago in Montreal. We drank free beer together in the hospitality suite at a literary conference in a hotel. And look at us now, I say.

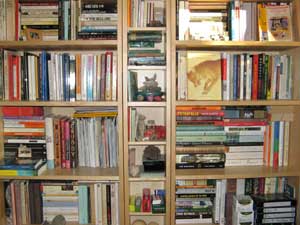

The Croatian Novelist heads off into the day. The Russian Novelist and I go used book shopping. He’s still carrying the books he gave me yesterday. They’re heavy but he doesn’t complain. He is a good boy, the Russian Novelist. We buy more books.

New York is so big. The Russian Novelist lives in Astoria. He’s meeting someone in Manhattan at 6:30 and doesn’t have time to go home in between. So our date goes on about four hours too long. Maybe a good editor will know what to do about this.

There’s a hole in the plot here, where I take a nap.

Late that night I have dinner in Chinatown with an old friend from Art School in Montreal, his wife and some friends of theirs. Art School Friend and his wife are late because their babysitter was late. Their friends are late because Pell Street is very hard to find, especially if you’re not from New York. Better late than never. We are all happy to see each other and we have a wonderful meal. The occasion: it’s Art School Friend’s wife’s birthday. It’s also Chinese New Year. Happy Birthday and Happy Year of the Pig.

Sunday I meet a Biographer for brunch in the West Village. She’s not my biographer! We’re just friends. We have an abstract and expressionistic conversation. I tell the Biographer how to set up a blog. She tells me how to buy a house in the country. I tell her Yaddo stories. She says: You seem exhilarated and sleepless at the same time, a neat trick.

I’ve accumulated so many books I have to buy a new bag. I shop in between appointments.

At 5PM I meet my Favourite Short Fiction Writer Friend from Ucross for an early dinner in the East Village. Is this too geriatric an hour to be eating, she asks? She brings me a book. I bring her a photo album. We pore over pictures of Wyoming and tell each other stories non-stop until it’s time to meet her boyfriend for drinks. An audience! We repeat our stories for him. And laugh so hard we cry. We can’t help it. We’re Short Fiction Writer Friends; even we know short stories are better the second time around.

Bag shopping isn’t going very well so Monday I combine it with shoe shopping. I don’t find a bag, but I do find a pair of shoes. I meet Favourite Short Fiction Writer Friend at the Strand. I buy more books. We go for a drink. We cannot understand why we don’t live in the same city. We go to Trader Joe’s. We cannot understand why the line-up circles the store. Favourite Short Fiction Writer Friend says it will move quickly. I almost but don’t quite lose my mind. Somehow we endure this ordeal.

Free at last we hike our wine, bread, blueberries and cheese down to Spring and Bowery for a Ucross reunion at afore mentioned sunny tenement turned charming studio. Only it’s not sunny now because it’s night. More specifically, it’s Ucross Reunion Night! We are: our host the Turkish Fibre Artist, Favourite Short Fiction Writer Friend (who is actually working on a novel now), Canadian Novelist (who has been living in NYC for nine years), Very Tall Composer (originally from Milwaukee?) and me. We agree: we all look the same. We dine on lentil soup, blood orange salad, wine and cheese, and delicious conversation.

And then suddenly time’s almost up. I run around Tuesday, buy a bag, and pack it. Then out again in the evening for a brief visit with another Painter Friend from Yaddo. We meet at the Frick. I don’t recognize her at first, not in her painting clothes. She has free passes. The collection is so familiar to both of us that we talk our way through it, pausing for our very favourites, until there we are out on the street saying: so good to see you again, saying goodbye. On the way home I buy another book.

Somehow I manage to pack thirty or so new books into what bags I have. More the miracle, in the morning I manage to drag them dead weight the eight blocks up to Port Authority. And I have a mercifully uneventful bus ride home.

I’m home now. And my bookshelves are at capacity.

. . . . .