J. R. Carpenter

drawing by Sherwin Tjia

bio

blog

book

[Mile End, Montreal, Quebec, Canada]

I moved to Montreal in 1990 and have lived in the Mile End since 1992. I have been using the Internet as a medium for the creation and dissemination of experimental texts since 1993. I made my first web-based writing project in 1995. And I made my first Montreal-based project in 2006. Given my preoccupation with place, why did it take me so long to take up the topic of Montreal in my work?

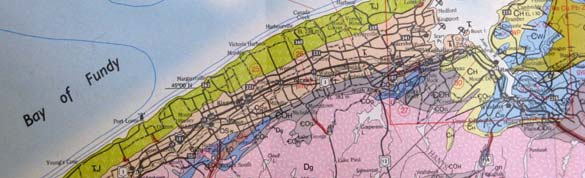

[Geological Map of the North Mountain of Nova Scotia]

I was born on a farm in rural Nova Scotia. I went to a three-room schoolhouse - there were six kids in my grade. In those days, in those parts, people used to say: "You're not from here until you have a grandfather buried here." My parents were immigrants, so even where I came from, I came "from away."

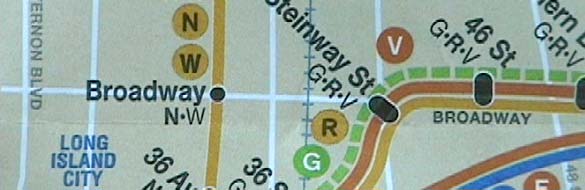

[NYC MTA Subway Map of Long Island City, Queens]

I spent most summers in New York City visiting my maternal grandparents. They lived in a high-rise apartment building in Queens. I thought they were immigrants, because they had such thick accents, but it turns out everyone in New York City talks that way. It took me a long time to figure out that in New York, I was the one with a foreign accent. I felt even less at home on Cape Cod, where my father's mother lived. Canadian novelist Anne-Marie MacDonald describes this condition of chronic displacement in her 2003 novel, As the Crow Flies:

If you move around all your life, you can't find where you come from on a map. All those places where you lived are just that: places. You don't come from any of them; you come from a series of events. And those are mapped in memory. Contingent, precarious events, without the counterpane of place to muffle the knowledge of how unlikely we are. Almost not born at every turn. Without a place, events slow-tumbling through time become your roots. Stories shading into one another. You come from a plane crash. From a war that brought your parents together.It was the Vietnam War that brought my parents together. My father was draft-evader. And, we soon discovered, a marriage evader. After my parents divorced we moved around a lot: every year a new place, new house, new friends, new school. Perhaps this explains why my short stories are so short and why there are so many of them.

Anne-Marie MacDonald, As The Crow Flies, Toronto: Knopf, 2003, page 36.

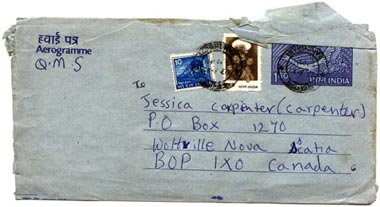

When you grow up in a different country than every one you're related to you write a lot of letters. I'm pretty sure this is how I became a fiction writer: I kept trying to explain where I lived to people who'd never been there before. I wrote a lot of letters to my grandmother in New York City. She rarely wrote back. I guess she felt that New York City, centre of the known universe, needed no further explanation. I corresponded regularly with pen pals in Italy, India and Somalia, and generally spent my time wishing I were somewhere else.

One of my favourite books of all time is The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster, illustrated by Jules Feiffer. The main character is a boy named Milo, who didn't know what to do with himself - not just sometimes, but always. "Wherever he was he wished he were somewhere else, and when he got there he wondered why he'd bothered." One day Milo comes home from school and finds an enormous package in his room containing the following items: One genuine turnpike tollbooth; three precautionary signs; assorted coins for use in paying tolls; one map, up to date and carefully drawn by master cartographers, depicting natural and man-made features; and one book of rules and traffic regulations, which many not be bent of broken. Having lots of time on his hands and nowhere better to be, Milo assembles the tollbooth, hops in a small electric automobile he just happened to have kicking around in his room, drives through the tollbooth and proceeds to have many clever and pun-filled adventures. He befriends a watchdog named Tock (tic-tock, tic-tock). Together they travel through Dictionopolis to Digitopolis and (I hope I'm not giving too much away) rescue Rhyme and Reason from the Mountains of Ignorance. No one told him it was impossible to do this until after he'd done it!

One of the three precautionary signs that came with the Phantom Tollbooth advised: HAVE YOUR DESTINATION IN MIND. Milo consulted the map, also provided:

It was a beautiful map, in many colors, showing principal roads, rivers and sear, towns and cities, mountains and valleys, intersections and detours, and sites of outstanding interest beautiful and historic.

The only trouble was that Milo had never heard of any of the places it indicated, and even the names sounded most peculiar.

"I don't thing there really is such a country," he concluded after studying it carefully. "Well, it doesn't matter anyway." And he closed his eyes and poked a finger at the map.

[A Map of the Literary Landscape of The Phantom Map, by J. R. Carpenter]

[A Map of the Literary Landscape of The Phantom Map, by J. R. Carpenter]The first time I read The Phantom Tollbooth I was nine years old. I was in the fourth grade. I wrote a book report about it on single sheet of foolscap. It's the only piece of schoolwork I still have from those years. I wrote: "My book took place in an amaganary world witch you enter through the phantom tollbooth. Its realy like a world in a world."

On the back I drew a map of Milo's route beyond Expectations, through the Doldrums, into Dictionopolis, past the Sea of Knowledge, onward to Digitopolis and upward into the Mountains of Ignorance to rescue Rhyme and Reason from the prison there. The map I drew in no way resembles the map provided inside the front cover of the book. I wonder, in retrospect, if I even noticed that a map had already been drawn; so intent was I on envisioning for myself this "amaganary" world.

HAVE YOUR DESTINATION IN MIND.

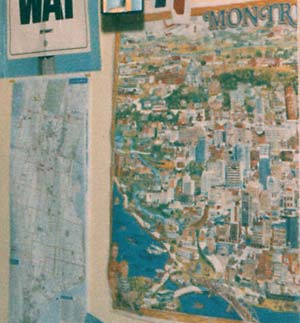

I was twelve years old when I decided I'd move Montréal. Montreal might just as well have been "amaganary" given how far away it was from my reality. At the time, no one I knew had ever been anywhere. Somehow I procured a cartoon map of the city depicting giant caricatures of famous Montrealers romping Godzilla-tall through the streets. The only one I recognized was Mordecai Richler, looming large over Saint-Urbain Street, his mugs well known to me from the back over of Jacob Two-Two and the Hooded Fang.

[Cartoon map of Montreal. Left: in one house, the cartoon map of Montreal hangs above my bed next to a map of Manhattan. Right: in another house the same map hangs over a bookcase]

This map thumb-tacked above my bed I read every Montréal author I could get my hands on, immersing myself in the literary Montréal Irving Layton evoked in his 1985 autobiography Waiting for the Messiah where there was only: "writing poetry and breathing poetry and talking poetry and nothing else had any reality." I got no extra credit in high school, for memorizing A. M. Klein poems. I fell in love with, and secretly wanted to be, the nude girl in Leonard Cohen's 1958 poem Snow Is Falling:

Snow is falling.What was a Montréal language? I was dying to know.

There is a nude in my room.

She surveys the wine-coloured carpet.

She is eighteen.

She has straight hair.

She speaks no Montreal language.

[aerial view of Montreal]

I moved to Montréal the minute after high school, which hardly seemed soon enough. If you would have told me back then that I'd spend the next fifteen years writing about rural Nova Scotia I would not have believed it. But that, of course, is precisely what happened.

In one of my earliest electronic literature projects, The Mythologies of Landforms and Little Girls [1996] a map of Nova Scotia forms the central image of the work and serves as the interface of the opening page. I began writing the narrative text of Mythologies in 1994 and quickly realized that not only did the story have no real beginning, middle or end, it did have lots of diagrams and intertextual incursions that I had no idea how to insert into the narrative.

Further, as I soon discovered, it's quite difficult to get a short story published in print - getting a story with pictures in it published in a literary journal was next to impossible. So I set out to find a medium better suited to my needs. In an essay published that same year, "What's a critic to do?: Critical Theory in the Age of Hypertext", George P. Landow observed:

Further, as I soon discovered, it's quite difficult to get a short story published in print - getting a story with pictures in it published in a literary journal was next to impossible. So I set out to find a medium better suited to my needs. In an essay published that same year, "What's a critic to do?: Critical Theory in the Age of Hypertext", George P. Landow observed:

The very idea of hypertextuality seems to have taken form at approximately the same time that poststructuralism developed, but their points of convergence have a closer relation than that of mere contingency, for both grow out of a dissatisfaction with the related phenomena of the printed book and hierarchical thought.

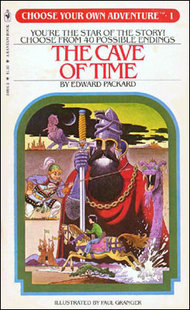

I built the hypertext version of The Mythologies of Landforms and Little Girls in 1996. The layout of the map interface on the main page was inspired by the paper placemats one used to find in tourist restaurants around Nova Scotia - an outline of the provence a map dotted with attractions. The narrative structure as a whole owes much to the Chose Your Own Adventure novels that were popular when I was a kid in the 1980s. The reader could enter the story at any point, and read in any order. Within the narrative, I used geological metaphors to distance myself from Nova Scotia, and childhood in general, by relegating them to an even more distant past.

I built the hypertext version of The Mythologies of Landforms and Little Girls in 1996. The layout of the map interface on the main page was inspired by the paper placemats one used to find in tourist restaurants around Nova Scotia - an outline of the provence a map dotted with attractions. The narrative structure as a whole owes much to the Chose Your Own Adventure novels that were popular when I was a kid in the 1980s. The reader could enter the story at any point, and read in any order. Within the narrative, I used geological metaphors to distance myself from Nova Scotia, and childhood in general, by relegating them to an even more distant past.

In some other millennia, the southern shores of Nova Scotia likely kissed the lip of Morocco or nuzzled below the chin of Spain. The force of their embrace was evidenced by a great mountain range, which slid down the long fault of their tectonic bodies...

[These are strange times indeed, when mountains love oceans...]

Cartography is arguably a literary invention - maps offer a singular point of view defined by a specific vocabulary. We imagine our anarchic, moveable, anonymous world in the guise of a readable map. And we labour under the illusion that we can know the world by naming it. Looking back at my early web projects, I see them now as "sites" of longing for belonging, small stand-ins for home.

Many of my early web works were in black and white, because that's what colour photocopies come in. For a digression into my love of the photocopy, read: A Little Talk About Reproduction.

Many of my early web works were in black and white, because that's what colour photocopies come in. For a digression into my love of the photocopy, read: A Little Talk About Reproduction. The Cape [2005] has a similar visual aesthetic to Mythologies, in part because some of the sentences in The Cape had been kicking around in my brain since the early 1990s. The story seemed too simple to count as a story until I found a copy of a Geologic Guide to the Cape Cod National Seashore from 1979. The images from this scientific publication became the stand-ins for non-existant photographs from the Cape Cod based branch of my family. Because The Cape is in the first person, people tend to think it is a true story. Cape Cod is a real place, but the people and events in The Cape are fictional. The maps are not to scale and the photographs have all been retouched. The moving images that resemble old home movies are actually still images being "pushed" across the screen by a DHTML time line. I tend to avoid Flash, and other software solutions. The more commercial, proprietary and predatory a place the Internet becomes, the more committed I am to using it in poetic and intransigent ways.

My grandmother Carpenter lived on Cape Cod in a Cape Cod House. My uncle also lived on Cape Cod but not in a Cape Cod House. The only time we ever went to visit it was winter but we walked on the beach anyway. These events happened so long ago that this whole story is in black and white.

[Roma Atlante Tascabile, Michelin, Edizioni per Viaggiare]

How I Loved the Broken Things of Rome is the most direct precursor to my current body of Montreal-based work. In 2002, after I'd lived in Montreal for a dozen years or so, I was starting to feel quite comfortable there. In order to reflect upn my adopted city, I decided I needed to recreate the experience of arriving in a new city with no knowledge of the language. I went to live for a time in Rome. I had no real plan, except to observe. Rome is among the largest and oldest continuously occupied archaeological sites in the world. Daily life in the modern, overcrowded, polluted, pickpocket plagued capital city of Rome is complicated, even for the locals. Romanticism and pragmatism must coexist. I rented an apartment in a working class neighbourhood where real Romans lived, where few people spoke English. My mundane struggles with public transportation, grocery shopping and the perplexing web of social vagaries reminded me acutely of my experiences, as an Anglophone, when I first moved to Montréal. I came to feel that understanding what was happening around me was a question of overcoming the dislocation of being a stranger. I collected the writings of many other travelers to Rome. In most cases (including my own) writing about the dislocations incurred by being a stranger in Rome is really an act of writing about home. How I Loved the Broken Things of Rome reflects upon certain gaps - between language and understanding, between the fragment and the whole, between the local and the tourist, between what is known (of history, of culture) and what is speculative.

Rome, if one does not yet know it, has an oppressingly sad effect for the first few days. Through the lifeless and doleful museum atmosphere it exhales, through the abundance of its pasts - fetched-forth and laboriously upheld pasts on which a small present subsists - through the immense over estimation, sustained by savants and philologists and copied by the average traveler in Italy, all of these disfigured and dilapidated things, which at bottom are after all no more than chance remains of another time and of a life that is not and must not be ours.Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet

[Rome Transit Map]

Entre Ville was my first major piece about Montréal. It was commissioned in 2006 by OBORO, an artists-run Gallery & New Media Lab in Montréal, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Conseil des arts de Montréal. To mark this anniversary the Conseil solicited commissions of new works in each of the artistic disciplines that it funds. Tasked with selecting the New Media commission, Daniel Dion - Director and Co-Founder of OBORO - felt that a web-based work had the most potential to be accessible to a wide range of Montrealers for the duration of the anniversary year and beyond. The commission included a four-week residency at the OBORO New Media Lab, where I edited the seventeen short videos included in the project. The resulting work, Entre Ville, was launched at the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal on April 27, 2006.

[The Island of Montreal]

Entre is the French word for "between," as in: entre nous, "between us". Ville is the French word for city. Montréal is an old city. It was founded in 1642 and was called Ville Marie until the 18th century. Driving into modern day Montréal, all signs point to centre ville, downtown. For the past fifteen years I've lived north of downtown in a neighbourhood called Mile End. For the past ten years I've lived on Saint-Urbain Street, on the same block Mordecai Richler grew up on. Inadvertently, I have come to occupy the literary landscape of the Montreal authors I read as a child in rural Nova Scotia. Tour busses still drive by looking for Mordecai, but mercifully his larger-than-life cartoon caricature no longer looms over our street.

[Saint-Urbain Street, Mile End, Montreal]

I work at home. My office window opens onto a jumbled intimacy of back balconies, backyards and back alleys. Daily my dog and I walk through this interior city sniffing for stories. Entre Ville is a text of walking, and a walk through texts. There are many authors of our neighbourhood. Some are famous, some less so. Through prose, poetry, photography, drawing, audio, video and various HTML, DHTML, CSS and javascripts, Entre Ville collates these texts, giving fictional, poetic and philosophical voices equal credence. And the neighbours get a say. It's a shared city, after all, this city entre nous.

[My Dog Isaac in our back alleyway]

Clicking on the Bibliotheque Mile End image at the top right of Entre Ville returns a list of authors from my neighbourhood and a selection of quotations from their works that describe the neighbourhood. One neighbour, poet and classicist Anne Carson, writes in The Life of Towns: "Towns are the illusion that things hang together somehow…." Montréal is both literally and figuratively a French-speaking island. The second largest French-speaking city in the world, after Paris, it floats in North America where only 2% of people claim French as a first language. The second largest city in Canada, after Toronto, only 17% of its population claims English as a first language. It's a complicated place to live, especially if you come from away. But things hang together somehow… Montréal's been very good to me.

Clicking on the Bibliotheque Mile End image at the top right of Entre Ville returns a list of authors from my neighbourhood and a selection of quotations from their works that describe the neighbourhood. One neighbour, poet and classicist Anne Carson, writes in The Life of Towns: "Towns are the illusion that things hang together somehow…." Montréal is both literally and figuratively a French-speaking island. The second largest French-speaking city in the world, after Paris, it floats in North America where only 2% of people claim French as a first language. The second largest city in Canada, after Toronto, only 17% of its population claims English as a first language. It's a complicated place to live, especially if you come from away. But things hang together somehow… Montréal's been very good to me.

Entre Ville was a long time in the making. I sketched the line drawing that became the user interface - a block of typical Montréal apartments - in 1992, while apartment hunting in the Mile End. I spent the next fifteen years learning the vocabulary of the neighbourhood. I don't mean the vocabulary of French, English, Italian, Greek, Portuguese, Yiddish or any of the other languages spoken in the Mile End. I refer rather to the cumulative vocabulary of neighbourhood: the aural, audio, visual, spatial, tactile, aromatic and climatic vocabulary of community.

I have attempted to present Entre Ville in this vernacular. To tell it like it is: Ours is not the nicest alley in the neighbourhood, but it's not the worst one either. Kitchen gardens and garbage heaps coexist with wildflowers and dog shit. Graffiti and grape vines vie for attention. Hand-painted signs warn: defense d'achets, defense du stationez. Cooking smells and laundry lines crisscross the alleyway one sentence at a time.

How does one learn the language of all this? One studies, of course. In The Life of Towns Anne Carson writes: "I am a scholar of towns… To explain what I do is simple enough. A scholar is someone who takes a position. From which position, certain lines become visible. You will at first think I am painting the lines myself; it's not so. I merely know where to stand to see the lines that are there."

How does one learn the language of all this? One studies, of course. In The Life of Towns Anne Carson writes: "I am a scholar of towns… To explain what I do is simple enough. A scholar is someone who takes a position. From which position, certain lines become visible. You will at first think I am painting the lines myself; it's not so. I merely know where to stand to see the lines that are there." From the position of my office window I can't help but learn the lives of my most immediate neighbours. Their voices barge into whatever I'm writing. Sometimes they take over. Entre Ville is based on one such neighbour-interrupted poem, Saint-Urbain Street Heat, which was originally published on NthPosition.com, a literary journal based in the UK. In the opening verse of Saint-Urbain Street Heat:

All the kitchen

All the kitchen back doors stand open -

sticky arms flung open -

imploring, in a heat-rashed prayer:

Deliver us unto

the many gods

of Mile End.

Note that Saint-Urbain Street Heat is not quite written in a first person point of view. Our proximity disallows singularity.

In an intimacy

born of proximity

the old Greek lady and I

go about our business.

Foul-mouthed for seventy,

her first-floor curses fill

my second-floor apartment;

her constant commentary

punctuates my day.

We go about our business. Nous autres. We're poor. It's hot. No one has air conditioning. This is common, a shared experience. Saint-Urbain Street Heat is a long hot sweaty heat-wave poem. Many people who have never been to Montréal in the summer refuse to believe how hot it gets. But we know. Our literature is drenched in the sweat of our summers. The Saint-Urbain Street heat is palpable in Mordecai Richler's 1955 novel, Son of a Smaller Hero:

The sky was a fever and there was no saying how long a day would last or what shape the heat would assume by night. There were the usual heat rumours about old men going crazy and women swooning in the streets and babies being born prematurely. When the rains came the children danced in the streets clad only in their underwear and the old men sipped lemon tea on the balconies and told tales about the pogroms of the czar.

Most Montréal apartments have two balconies: one on the street front and one in the back alley rear. A common ground in our oft-divided city, an extra room, a storage space, a slim slice of outdoors for inner city apartment dwellers, the balcony becomes a stage upon which dramas unfold, from which orations issue. In David Fernario's bilingual 1980 play Balconville, three families sit on their balconies in the heat of a Montréal summer.

Most Montréal apartments have two balconies: one on the street front and one in the back alley rear. A common ground in our oft-divided city, an extra room, a storage space, a slim slice of outdoors for inner city apartment dwellers, the balcony becomes a stage upon which dramas unfold, from which orations issue. In David Fernario's bilingual 1980 play Balconville, three families sit on their balconies in the heat of a Montréal summer.

JOHNNY: "Whew, hot. You going anywhere this summer?"Balconville is a Franglais word, Montréal slang. In French, a "balcony" is a galerie. Like the visual art gallery, the galerie is a site charged with potential. It is an in-between space, an entrespace in which the private unfolds in public display. In Nicole Brossard's 1986 novel French Kiss, the balcony operates as a threshold of enunciation: "One struggles without voice to forge a voice the way a wrought-iron balcony suddenly gives access to the city's far-off sounds." Summer long conversations echo across the alleyway in call-and-answer strophe / antistrophe, clothesline curtains reeling in and out between the acts.

PAQUETTE: "Moi? Balconville."

JOHNNY: "Yeah. Miami Beach."

Don't be fooled. I have poetic ideas about neighbourhood, not romantic ones. Entre Ville is hot, loud, crowded and dirty. And, much to my surprise, even after 15 years of living in the city, it turns out that I am still rural, solitary and occasionally misanthropic. Writing about my more trying neighbours has given me a soft spot for them though. Two months after the launch of Entre Ville the old Greek lady next door was evicted from her apartment of 23 years; we watched from our balcony as the discarded detritus of her life accumulated in the alleyway, where strangers rifled through for treasures. Including us. Entre Ville has become a document of gentrification and its erasure. Mile End is changing. Our building is for sale. We may very well be next.

I write about my neighbours acutely aware that I write from amongst them. Gossip is rampant on our street, there to overhear, if you're listening for it. Stories pass from balcony to balcony. Voices carry. Word gets around, especially online. Occasionally the neighbourhood writes me an email. Like this one:

I was sitting at my mom's (no internet at home yet) eating millet pie with ketchup (a bit too dry). I clicked on Wannatakepicture. There was my mom's house. There was the window i was staring out of (blankly) moments before. And there was the voice of Mr. G, the Portuguese landlord. Nice garden. Mom was chuffed. J. M.How one reads or writes the texts and textures of neighbourhood depends entirely on one's point of view. Do you live here? Are you a parent or a child, a cat or a dog, a bicyclist or in a SUV? Word on the street is, novelist Heather O'Neill lives a few doors down from me. Her award winning 2006 novel, Lullabies for Little Criminals, offers up a disconsolate twelve-year-old's point of view of the alley:

The back alley behind Lauren's house looked the way the world would look if a child had built it. Some underwear and a couple T-shirts that had fallen from clotheslines lay on the pavement. A single sneaker was stuck up on a fence post. There was a toy bucket with rocks in it and a sled that had been left behind from a day when there had been snow on the ground. A wooden door leaned against a wall, leading nowhere. There was a lamp and a bathroom sink in the same garbage heap. You'd think that these houses were being blown apart by the wind, the way that pieces of them were lying about. Not one for them would be a match for the Big Bad Wolf.

Whatever I might say about multiplicity, Entre Ville privileges a pedestrian point of view. If you click on the dog at the lower left-hand corner of Entre Ville, you will see a new text appear on the note book page. Sniffing For Stories was written for an interdiciplinary walking tour of Mile End in 2006. Participants walked up the alleyway listening to and audio track of this text mixed with sounds of the dog and the alleyway. In Wanderlust: A History of Walking, Rebecca Solnit likens walking to writing: "The walking body can be traced in the places it has made; paths, parks, and sidewalks are traces of the acting out of imagination and desire." In The practice of Everyday Life Michel de Certeau suggests that the "ordinary practitioners of the city" cannot read this writing: "They are walkers… whose bodies follow the thicks and thins of an urban "text" they write without being able to read… unrecognized poems…" Perhaps if de Certeau had lived in the neighbourhood he wrote that about he'd have seen things differently. He claims that: "To walk is to lack a place." My dog and I humbly disagree. For the eight-and-a-half years of his lifetime we've been walking up and down our back alleyway:

Whatever I might say about multiplicity, Entre Ville privileges a pedestrian point of view. If you click on the dog at the lower left-hand corner of Entre Ville, you will see a new text appear on the note book page. Sniffing For Stories was written for an interdiciplinary walking tour of Mile End in 2006. Participants walked up the alleyway listening to and audio track of this text mixed with sounds of the dog and the alleyway. In Wanderlust: A History of Walking, Rebecca Solnit likens walking to writing: "The walking body can be traced in the places it has made; paths, parks, and sidewalks are traces of the acting out of imagination and desire." In The practice of Everyday Life Michel de Certeau suggests that the "ordinary practitioners of the city" cannot read this writing: "They are walkers… whose bodies follow the thicks and thins of an urban "text" they write without being able to read… unrecognized poems…" Perhaps if de Certeau had lived in the neighbourhood he wrote that about he'd have seen things differently. He claims that: "To walk is to lack a place." My dog and I humbly disagree. For the eight-and-a-half years of his lifetime we've been walking up and down our back alleyway:

That's eight-and-a-half years of up and eight-and-a-half years of down. Nine thousand three hundred laps of toenails clicking on cracked concrete. Trail zigzagging, long tail wagging, long tongue lolling, dog tags clacking. Ears open, eyes darting, nose to the ground.We walk like we own the place. We walk to write the place, to collect, collate and annotate the multitude of texts generated by the occupants of Entre Ville. We try to read between the alleyway's long lines of peeling-paint fences spray painted with bright abstractions and draped with trailing vines. In French Kiss Nicole Brossard describes the meta-text of walking as:

Writing that feeds on zigs and zags and detours… Isn't on every streetcorner but roams the streets, traces its course through them… the narration of the inner odyssey in terms of Montréal's geography, its contours and harsh angles, sidestreets and lanes sharing the circulatory problems with the major arteries, from the heart of the city to the epicentre of oneself, the target and motive source.Entre Ville is a poem. It has been published in print and online, with and with out pictures, and it has been read aloud to audiences large and small in Montréal and places far away from Montréal's back alleyways. In the early days of the Internet, alarmists and advocates alike proclaimed that digital media heralded the end of the book. Yet, as Derrida had already noted in Writing and Difference:

"The question of the book could only be opened if the book was closed… only in the book, coming back to it unceasingly, drawing all our resources from it, could we indefinitely designate the writing beyond the book."

"The question of the book could only be opened if the book was closed… only in the book, coming back to it unceasingly, drawing all our resources from it, could we indefinitely designate the writing beyond the book." In its book iteration Entre Ville is very small. Photocopied and stapled, the Entre Ville mini-book recycles images cut from some children's textbooks we salvaged from the old Greek lady's moving day garbage. It's sold at readings and events and through DISTROBORO, a neighbourhood network of cigarette machines re-purposed to sell cigarette-pack-sized art for two dollars.

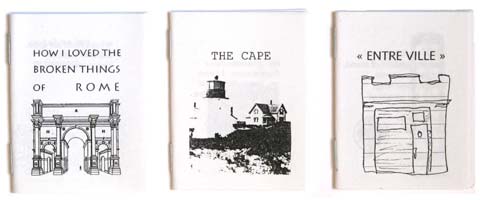

[Mini-Book iterations of How I Loved the Broken Things of Rome, The Cape and Entre Ville]

In its web iteration, Entre Ville's verses scroll the alleyway, popup in windows - altered - and then disappear. The user interface is an image of a blank book upon which a few lines of city have been hastily sketched. Roll the mouse over windows and doors as you might scan your eyes over a cityscape. Occasionally you will catch a glimpse of an interior. And, as in Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities, "It also happens that … when you least expect it, you see a crack open and a different city appear. Then, an instant later, it has already vanished."

I moved to Montreal on the night train.

I've lived in eight neighbourhoods since.

Each has had a different quality of sleep.

There are eight hours for sleeping in. There are four quarters in an hour. There are many more quarters in a city. Some quarters never sleep, or so they say. Others seem to be built for dreaming in. The piece begins, as so much of my work has, with the transition from Nova Scotia to Montreal. Specifically, in this case, on the over-night train from Halifax to Montreal:

There are eight hours for sleeping in. There are four quarters in an hour. There are many more quarters in a city. Some quarters never sleep, or so they say. Others seem to be built for dreaming in. The piece begins, as so much of my work has, with the transition from Nova Scotia to Montreal. Specifically, in this case, on the over-night train from Halifax to Montreal:

The night train tunnels termite-determined through silent miles of bark-black forest. Passengers forage for provisions, restless-long this expedition; minds race ahead, pace coach and sleeping class compartments listing along the fleuve Saint-Laurent, dip-slice-glide-lurch-swaying, steady-forward, slow as the Voyageurs' paddles.These are les huit quartiers du sommeil de Montréal - 1990-2006: Car Crash Sleep, Bamboo Blind Sleep, Waterbed Sleep, Louvered Door Sleep, Purple Parakeet Sleep, Break and Enter Sleep, Gondola Sleep and Greek Sleep. The Epilogue does not take place after all of these sleeps - I have placed it at the end because it is quite possibly one of my first attempts at writing Montreal.

From your house I fled gently, and laughed in the evening. Too weak to dance. Timid in the aftermath. I traveled smooth through slow tunnels, wore thin the scenery and left grey traces. Dawn. I walked on. Heavy. Soft bones on Sunday. Slow and sad through the park of young boys slim and quick. Until finally the rain came, danced three-four time emphatic. I turned at random. At a stair near a fountain, I turned toward home.

[Fountain in Carré St-Louis, Montreal]

This brings me to the present moment. And, as Virginia Woolf asks in Orlando, "What more terrifying revelation can there be than that it is the present moment? That we survive the shock at all is only possible because the past shelters us on one side and the future on the other."

After a childhood spent in rural Nova Scotia dreaming of moving to Montreal and then fifteen years spent in Montreal writing of rural Nova Scotia, I had finally learned how to write about my small corner of Montreal, in the vernacular of neighbourhood, in the present moment. And then the whole neighbourhood changed.

My most recent work, in absentia [2008], addresses issues gentrification and its erasures in the Mile End neighbourhood of Montreal. in absentia is a Latin phrase meaning "in absence." I'm drawn to the contradiction inherent in being in absence. In recent years many long-time low-income neighbours being forced out of Mile End by economically motivated decisions made their absence. So far fiction is the best way I've found to give voice these disappeared neighbours, and the web is the best place I've found to situate their stories. Our stories. My building is for sale; my family may be next.

Faced with imminent eviction I've begun to write about the Mile End as if I'm no longer here, and to write about a Mile End that is no longer here. By manipulating the Google Maps API, I am able to populate "real" satellite images of my neighbourhood with "fictional" characters and events. I aim to both literally and figuratively map the sudden disappearances of characters, fictional or otherwise, from the places, real or imagined, where they once lived; to document traces people leave behind when they leave a place, and the stories that spring from their absence. in absentia is a web "site" haunted by the stories of former residents of Mile End, a slightly fantastical world that is already lost but at the same time is still fully known by its inhabitants: a shared memory of the neighbourhood as it never really was but could have been.

Faced with imminent eviction I've begun to write about the Mile End as if I'm no longer here, and to write about a Mile End that is no longer here. By manipulating the Google Maps API, I am able to populate "real" satellite images of my neighbourhood with "fictional" characters and events. I aim to both literally and figuratively map the sudden disappearances of characters, fictional or otherwise, from the places, real or imagined, where they once lived; to document traces people leave behind when they leave a place, and the stories that spring from their absence. in absentia is a web "site" haunted by the stories of former residents of Mile End, a slightly fantastical world that is already lost but at the same time is still fully known by its inhabitants: a shared memory of the neighbourhood as it never really was but could have been.

What traces do people leave behind when they leave a place?Themes of place and displacement pervade my fiction and electronic literature, yet place long remained an abstract, elusive notion for me. Perhaps because for many years I wrote about long ago places attempting to inhabit pasts that could never be mine. Mapping the minutia of my most immediate surroundings has made my notion of place less abstract and more socially engaged. Increasingly, my work is collaborative. To better represent the multi-lingual nature of my neighbourhood and to ensure a multipule point of view, for in absentia I invited a cast of English and French writers from my neighbourhood to pen "postcards" to and from former tenants, fictional or otherwise, displaced by gentrification. in absentia was presented by DARE-DARE Centre de diffusion d'art multidisciplinaire de Montréal - an artist-run centre that operated out of a trailer parked in a park without a name on the northern-most border of Mile End until recently.

What stories spring from their absence?

The mobile office has since the vacant lot that was its home for two years and move towards Montréal's downtown, in Cabot Square, corner Sainte-Catherine and Atwater. in absentia marked the end of DARE-DARE's Dis/location: projet d'articulation urbaine in the Mile End's parc sans nom. DARE-DARE was evicted by the city to make room for a parking lot. There goes the neighbourhood. Where we would park a garden so many people plant cars.

The mobile office has since the vacant lot that was its home for two years and move towards Montréal's downtown, in Cabot Square, corner Sainte-Catherine and Atwater. in absentia marked the end of DARE-DARE's Dis/location: projet d'articulation urbaine in the Mile End's parc sans nom. DARE-DARE was evicted by the city to make room for a parking lot. There goes the neighbourhood. Where we would park a garden so many people plant cars.

If, as Anne-Marie MacDonald suggests, "[when] you move around all your life, you can't find where you come from on a map," at least, through a sustained (stubborn) practice of writing and rewriting contingent stories of precarious past events it is possible, on occasion, to locate one's present location. Even if, in the very act of writing of it, one's present location becomes fictional.

If, as Anne-Marie MacDonald suggests, "[when] you move around all your life, you can't find where you come from on a map," at least, through a sustained (stubborn) practice of writing and rewriting contingent stories of precarious past events it is possible, on occasion, to locate one's present location. Even if, in the very act of writing of it, one's present location becomes fictional."I packed my rucksack with socks, canteen, pencils, three empty notebooks. I took no maps, I cannot read maps - why press a seal on running water? After all, the only rule of travel is, Don't come back the way you went. Come a new way." Anne Carson, "The Anthropology of Water," in Plainwater, NY: Vintage, 1995, page 123.

For more links and reading lists, visit:

lapsus linguae (a blog of sorts)

J. R. Carpenter || bio || electronic literature || publications || talks || blog

J. R. Carpenter || bio || electronic literature || publications || talks || blog