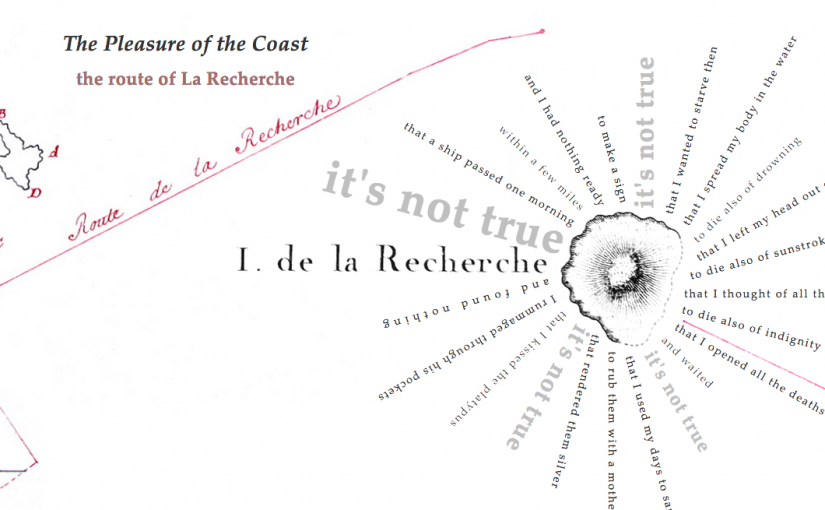

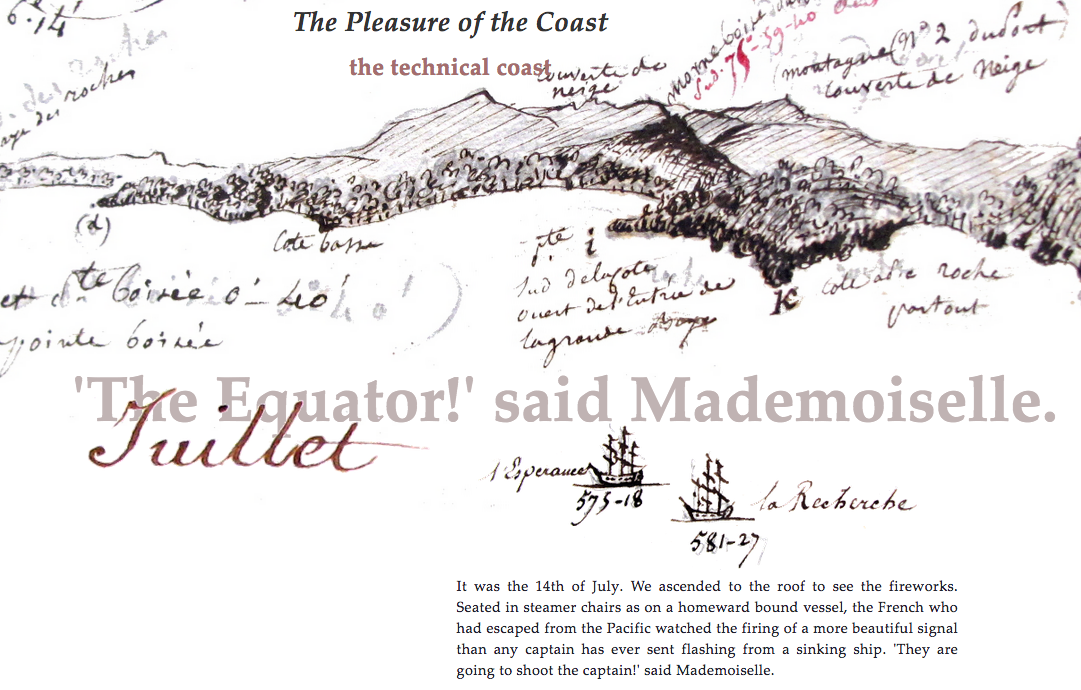

I’m delighted to announce the launch of a new bilingual web-based work of digital literature today, Bastille Day. In English the work is called The Pleasure of The Coast: A Hydro-graphic Novel. In French, Le plaisir de la côte : une bande dessinée. It’s a story of the western mapping of the South Pacific, rather too big for most phones. Best viewed on a laptop or tablet. It’s available here: http://luckysoap.com/pleasurecoast

This work was commissioned by the « Mondes, interfaces et environnements à l’ère du numérique » research group at Uinversité Paris 8, supported by Labex Arts-H2H (now merged with ArTeC), in partnership with the Archives Nationales in Paris. It was presented as a work in progress at « Des machines imaginantes médiatrices de fiction ? » 11-13 décembre 2018 à l’Université Paris 8. The (more or less) completed work will officially launch at Electronic Literature Organization Conference & Media Arts Festival 15-17 July 2019 at University Collage Cork in Ireland.

An ocean of thanks to Arnaud Regnauld and Pierre Cassou-Nogues at Université Paris 8; to Françoise Lemaire, Nadine Gastaldi, and Clothilde Roullier at the Archives nationales; and to Robert Sheldon and Stelios Sardelas for ground support in Paris.

For anyone unfamiliar with French naval history, some background information may be useful. In 1785 King Louis XVI appointed Lapérouse to lead an expedition around the world. The aim of this voyage was to complete the discoveries made by Cook on his three earlier voyages to the Pacific.

On the 1st of August 1785, Lapérouse departed Brest with no less than ten scientists aboard. On the 10th of March 1788, Lapérouse departed the English Colony at new South Wales, Australia. He was never seen by European eyes again.

To the English ear, the name Lapérouse sounds a lot like the verb ‘to peruse’ — to scan or browse, to read through with thoroughness, to survey or examine in detail. The dictionary cautions, the word ‘peruse’ can be confused with the verb ‘to pursue’ — to follow in order to overtake, to strive to gain, to seek to attain, to proceed in accordance with a method, to carry on or continue. The English word ‘pursue’ sound a bit like the French word ‘perdu’ — disposable, ruined, lost.

On 25 September 1791, Entrecasteaux departed from Brest in search of the lost Lapérouse. One of his two 500-ton frigates was named La Recherche. On board was a young hydrographer, Charles-François Beautemps-Beaupré (1766-1854), a close contemporary of the English hydrographer Francis Beaufort (1774-1857). Beaufort is perhaps most famous for the wind scale named after him, for measuring the force of the wind. Beautemps is an auspicious name for an ocean-going person, in need of fair winds. Once at sea, however, beau pré are few and far between.

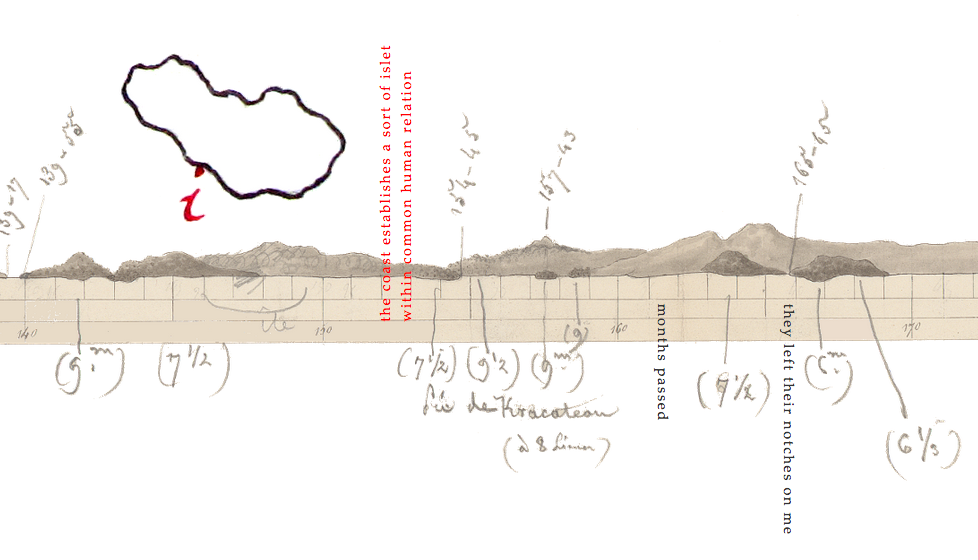

Finished sea charts are designed to be uniform in appearance, as precise as possible. The Archives nationales in Paris holds hundreds of sheets of drafts of charts made by Beautemps-Beaupré aboard La Recherche, and boxes of sketchbooks. A mix of drawing, writing, and numbers. The active marks of a practicing hand. Oak gall ink on rough paper. Liquid lines of inquiry. Drawn onwards by a moving ship.

The title and much of the text in this work borrows from Roland Barthes, The Pleasure of the Text (1973). The word ‘text’ has been replaced with the word ‘coast’. This détourned philosophy is intermingled with excerpts from Beautemps-Beaupré’s Introduction to the Practice of Nautical Surveying and the Construction of Sea-Charts (1808). Artistry, philosophy, hydrography — what’s missing. Ah, yes, fiction. And women. This gap is filled by Suzanne, the first-person narrator of Suzanne et le Pacific. In this early novel by Jean Giraudoux, published in 1921, a young French woman wins a trip around the world. She becomes shipwrecked, and survives alone on a Pacific island in roughly the same region surveyed by Beautemps-Beaupré.

I have appropriated, exaggerated, détourned, corrected, and corrupted both the original French and the English translations of these texts. Who, then, is the author of this work? The author is not dead. The author is multiple: multimedia, multilingual, poly-vocal. “Which body?” Barthes asks, “We have several.” Imagine if Barthes were the bastard love child of Giraudoux but grew up to be a hydrographer instead of a philosopher. Or if Beautemps-Beaupré had secretly written a symbolist novel from the point of view of a female castaway. But for the web…

In French, the term ‘bande dessinée’ refers to the drawn strip. What better term to describe the hydrographic practice of drawing views of the coast from the ship? In English, the term for ‘bande dessinée’ is ‘graphic novel’. I’m calling this work a hydro-graphic novel.

The images in this work are a combination of my own photographs and digitisations generously made for me by the Archives nationales. More information on the text sources can be found within the work itself. Finally, I would note that this work is imperfectly bilingual. All errors in translation, transcription, and interpretation are my own.

http://luckysoap.com/pleasurecoast