November 2013 will mark twenty years since I got my first UNIX account. Things have changed a lot since then. The more proprietary, predatory, and puerile a place the internet becomes, the more committed I am to using it in poetic and intransigent ways. Over the next few months I will be looking for ways to use this anniversary as an opportunity to reflect on the dialectic between how far we’ve come, and how very far we have to go.

The following non-linear timeline of twenty years online is an expanded version of my contribution to “Aura in the Age of Computational Production,” a roundtable discussion with with Kathi Inman Berens, J. R. Carpenter, Leonardo Flores, David Jhave Johnston, Jason Edward Lewis, Erik Loyer, and Nick Montfort, to be held at Chercher le texte, ELO Paris 2013.

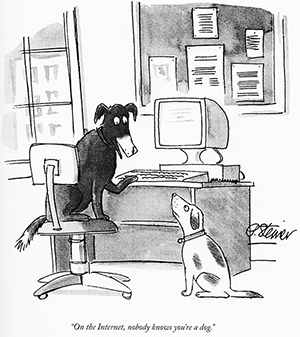

July 1993. The New Yorker published a cartoon by Peter Steiner depicting a dog sitting at a computer informing another dog sitting on the floor that: On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.

November 1993. I got my first Unix account in order to participate alt.arts.nomad, the USENET component of an exhibition by Ingrid Bachmann called Nomad Web: Sleeping Beauty awakes, which was the first networked-art project in Canada, as far as I know. On the internet, nobody knew I was a fiction writer. Not even me.

May 1995. I graduated from Concordia University, in Montreal, Quebec, with a BFA in Studio Art, with a concentration in Fibres and Sculpture, with distinction, approximately 1.1 months after Netscape Navigator 1.1 was released.

November 1995. I made my first web art writing project during a thematic residency at The Banff Centre for the Arts, as The Banff Centre was then known. The theme of the residency was Telling Stories: Telling Tales. I told them I was a writer, and they believed me. The web piece I made there was called Fishes and Flying Things. It remediated a paper zine printed from a QuarkExpress file stored on a 44 MB SyQuest cartridge which I still own but the contents of which I can no longer access. The images were digital scans of photocopies of borrowed books no longer in my possession. The text was based on the title of an installation art exhibition I had work included in Montreal at the time, of which, other than an event poster, no physical or documentary evidence remains. Upon my return from Banff to Montreal, my artist friends informed me that web-based work was elitist, because so few people could access it, and my writer friends assured me that the internet would never catch on. Fishes and Flying Things is still online and it still works.

November 1998. I gave an artist’s talk called A Little Talk About Reproduction at a web art exhibition called Maid in Cyberspace – Encore!, hosted by Studio XX, a feminist artist-run centre for technological exploration, creation and critique founded in Montreal in 1996. This talk reflected on the formal transition I’d made from zine to web, from the vast perspective offered by the passage of three whole years. On the internet, nobody knows how far we’ve come.

February 2010. I gave an artist’s talk called A Little Talk About Reproduction at In(ter)ventions: Literary Practice at the Edge, a gathering held at The Banff Centre. The first talk had been prognostic, to use Walter Benjamin’s term. By the time of the second, we might say that everything expected of the future had long since transpired. Except, we had no idea what to expect. We might say that in the age of computational production longevity lends aura to a work. Except. On the internet, nobody knows how far we have left to go.

June 2008. I made a web-based work called in absentia with the support of Dare-Dare, an artist-run centre which, at that time, was operating out of a trailer in a vacant lot in the Mile End neighbourhood of Montreal. The launch event was a six-hour outdoor neighbourhood block party attended by over a thousand people. The work was projected on the underside of a viaduct. There were DJ’s and bar-tenders and Port-o-Let portable toilets rented especially for the occasion. The police came six times. No arrests were made.

November 2012. Alexandra Saemmer suggested, in Evaluating digital literature: social networks, selection processes and criteria, a paper presented at Remediating the Social, Edinburgh, that in absentia“>in absentia can be considered part of the cannon because it is contained in certain academically-funded collections of digital literature. Which lends more aura to a digital work, a canonical status inferred from inclusion in collections, or hired Port-o-Lets and a police presence?

At 4:40PM on 1 April 2012. Andy Campbell tweeted a link to a blog post called The closed circles of elit in which he wrote: “I can’t see how electronic literature can really evolve though without being exposed to an audience outside of academia.”

At 4PM on 2 April 2012 I tweeted: “as an author of web-based #elit I’ve always assumed my audience to be people at work who are supposed to be doing other things“. William Gibson @GreatDismal re-tweeted this, to his 100,000 followers.

On the day I sat down to write this timeline, I Googled “On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.” On the internet, it says this is the most reproduced New Yorker cartoon of all time. Steiner has earned over $50,000 from its reprinting.

Endnote: The title “Aura in the Age of Computational Production” refers to Walter Benjamin’s essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1935). As the somewhat tongue-in-cheek tone of this timeline may suggest, I find the question of whether or not a work of digital literature can have “aura” to to be a non-nonsensical one. is computationally produced a new each and every time it is called upon for display on screen. The We can say a digital work may gain “aura” by virtue of its ‘spreadability,’ a concept put forth by Henry Jenkins, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green in Spreadable Media, but we won’t mean what Benjamin meant.