Ucross is too good to us. We don’t ever want to leave. Unless there’s a field trip. Then we’re up bright and early dressed in our warmest clothing and packing our own lunches.

On Wednesday Reed drove us to the Devils Tower National Monument. Reed’s a Wyoming native. He hadn’t been to Devils Tower since he was a kid. Jerome hadn’t been in seven years. The rest of us just hadn’t been.

We were eight people in one Suburban. We refrained from singing car songs. It’s a two and a half hour drive each way.

Flushed like pheasants from our Big Horn Mountain foothill hidey-hole, we flowed down the Clear Creek valley and out into the Coal Bed Methane Lands of Powder River Basin. On either side of the wide-open traffic-empty I-90, willy-nilly dirt roads spilled over drought-kaki slopes scared with wellheads, compressing stations, derricks, tailings ponds and open pit coalmines. All this mess and only 5% of the methane in the Powder River Basin have been developed. Mean and ugly things are being done to these high plains in order to obtain, at most, a year’s supply of natural gas.

I read somewhere that there are more mobile homes in Wyoming than in any other state. I don’t know if that’s per capita or otherwise. The suburbs of Gillette certainly are thick with them. Subdivisions sprawl down and out like varicose veins.

We push on, like the French fur traders did in the 1850s, into the Belle Fourche River Valley. The Black Hills is a whole other Wyoming. North of Moorcroft we see pine trees – lodge pole, ponderosa – after a month of leafless cottonwoods and bowed box elder this many pine trees boggle the mind.

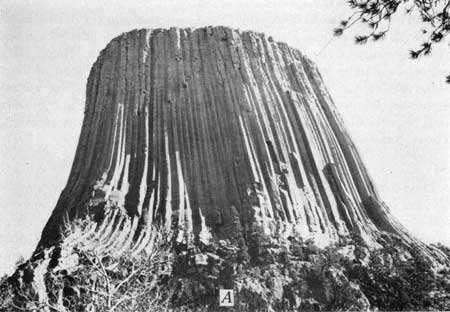

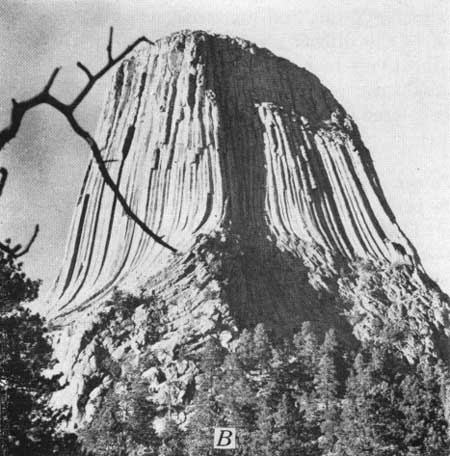

Plenty has been written about Devils Tower elsewhere. Here’s a a brief synopsis: 60 million years ago a mass of molten magma forced its way upward through layers of Jurassic era sedimentary rocks. As the igneous rock cooled underground it contracted and fractured into polygonal columns measuring 6 to 8 feet in diameter at their base and tapering gradually upward to about 4 feet at the top. Over millions of years the surrounding layers of softer sedimentary rock eroded, exposing the tower of hard igneous rock. At present, the tower towers 1,270 feet above the Belle Fourche River, at an altitude of 5,117 feet.

Archaeological investigations indicate that native peoples have visited the tower since prehistoric times. Many continue to value it as an important sacred place. The Lakota call the tower Mato Tipila, Bear Lodge. In 1875 one Col. Dodge of the US Geological society insisted the native name was Bad God’s Tower, which he twisted into Devils Tower. Some people just don’t listen. The name Devils Tower is an affront to the generations of Lakota, Crow, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, and Eastern Shoshone who continue to return to the tower and its surrounding landscape to carry out traditional rituals and ceremonies.

President Theodore Roosevelt designated Devils Tower the first US national monument on September 24, 1906, under the newly created Antiquities Act. Naming a 60 million year old rock an antiquity? Naming a first nations’ sacred sight a monument to conquering America? I don’t know where to begin.

We arrived two months and five days late for the hundredth anniversary celebrations. Reed says the site hasn’t changed since he was a kid. We had the 2km Tower Trail to ourselves; hiked heads flung back, the tower rising so steeply, it felt at times like we might topple over backward. It was a moving experience. People say that and I think: Yeah, sure, right. But it was. I’ll leave it at that.

The drive home was even more beautiful than the drive out. Reed let me hold the map. Everyone knows I love a map. The sun low we rose back up into the Big Horn foothills. A huge half moon hung over the Red Hills. Power lines raced along the road. Having gone so far out, returning, the Clear Creek ranches looked like home to us, looked familiar-dear to us. A Bald Eagle paused low over the creek beside US16 north of Buffalo. So close to us. Our avatar. It passed a heartbeat at eye level with us, feeling for its next updraft, wingspan wide as the Suburban. And then it was gone. Or we were. We all agreed that this was an omen, but had different ideas about what it might signify. Sermin will buy a ranch. Dinner will be good. We will never have to leave this place.

. . . . .